I was requested by a client to provide a mapping of my organizational maturity model and patterns of Kanban maturity, to Jim Shore & Diana Larsen’s Agile Fluency model which has been boosted by the support of Martin Fowler. The clients’ request was based out of the simple need that his organization is already (somewhat) familiar with Agile Fluency and hence, he wants me to be able to explain to his people how my model maps into a context they already understand. I decided there would be value in sharing my thoughts on this for broad consumption.

Introduction

If you aren’t familiar with the Agile Fluency model, you can read the original article here. I’ve known Jim Shore & Diana Larsen for 10 years or so. I bump into them on the conference circuit from time-to-time. Most recently, they were in Malmo for Oredev last November where I gave the opening key note on social engineering.

Jim and I have a lot of mutual respect while recognizing that we have very different approaches to improving agility. As Jim says, he practices “kaikaku” (large managed change) and not “kaizen” evolutionary, start with where you are now, change. Jim only works with clients willing to replace their existing system of software development with his Agile method. So we are two different ends of the spectrum. Also Jim tends to work in small scale – teams of 2 to 12 people and in small departments, where I have been working with clients attempting Enterprise Services Planning with the intent to scale up to 100,000 people. Having identified the differences, it is still possible to provide some insight into how you might map Agile Fluency to Kanban Patterns and Organizational Maturity.

Agile Fluency & Organizational Maturity Models

Figure 1. Agile Fluency Model

Figure 1 shows the Agile Fluency model reproduced directly from the original web site. Figure 2 shows my recent Professional Services Organizational Maturity Model (PSOMM).

Figure 2. Professional Services Organizational Maturity Model

If we were to look at the diagrams only, we might come to a fairly quick and simple conclusion, there is a 1-1 mapping at each level. “Start Building Code” would map directly to maturity level 1. “Focus on Value” 1-star Agile fluency appears to imply maturity level 2 – there is an ability to define a customer and a customer-valued piece of work and to direct people and teams based on customer-valued requests. There is a consistency of process and the elements that go with it. There is an implied change in culture to be more externally focused and to recognize that there is a customer and a concept of customer value which can be captured when defining customer requests for work. “Deliver Value” 2-star Agile Fluency appears to imply maturity level 3 – because the team can deliver value on the market cadence and this sounds like “consistency of outcome.” There is also an implication that there is a significant step up in skills in order to provide consistency of outcome. “Optimize Value” 3-star Agile Fluency seems to map to maturity level 4. There is a focus on optimizing the economic outcome and in driving real business benefit from the capabilities achieved in the lower levels of fluency. “Optimize for System” 4-star Agile Fluency appears to map directly to the concept of optimizing an organization and its service and product delivery capabilities at maturity level 5. So there it is, a simple 1-1 mapping!

If only it were that simple! I believe some deeper analysis is required. I do believe that Shore & Larsen’s intent is essentially similar to the five maturity levels and that we should accept the 1-1 mapping at face value, but some deeper analysis and insight is required to see where there are gaps – not with intent but with practical, pragmatic, actionable guidance for improving and moving up the ladder whether you think of it as Agile Fluency or organizational maturity.

The Trouble with “Value”

I was probably the first member of the Agile community to write with any substance on the topic of “value” and optimize economic performance from Agile methods, in the form of a 63,000 word book published in 2003. Around that time, the Agile community wasn’t sufficiently interested in topics such as “prioritizing iteration backlogs based on value” that my submission for the Agile 2003 conference was rejected. The state of the art in the Extreme Programming community was to prioirtize based on technical risk. Agile was largely an internally focused movement. Yes, there was mention of “value” in the Agile Manifesto but when it came to practical guidance there simply wasn’t any. At the time, I wrote Agile Management, I thought defining “value” was easy(ish). I was obsessed by physical goods industry literature on optimizing industrial process, such as The Theory of Constraints, and convinced that all we had to do was determine the value for features and then use that information to prioritize and hence optimize economic performance. Now 13 years later, I can tell you that I am less certain that ever that we know how to define “value” in any meaningful way that can lead to a deterministic approach to optimization of economic performance.

What does “value” mean? If you read the text of the Shore/Larsen article it appears to imply a fairly simple concept – “is this story of value to our customers?” Answering this question is fairly easy. So if we take it at that level, we would map that to organizational maturity level 2: we can identify a customer; and we understand what would represent meaningful value to that customer; we are capable of sifting out tasks, and other items of internal value that are not meaningful to the customer. So there is some improvement in alignment and unity of purpose. We have customer focus. Followers of the Kanban Method will recognize some synergies with the Values and Principles of the Kanban Method.

“The trouble with value” starts when you try to get beyond the notion of “is this valuable” and instead try to quantify the value. I spent two chapters of the Agile Management in 2003 trying to wrestle with this and frankly the conclusion would be, in most circumstances, professionally services work, cannot be reduced to a quantitative measure of value, at best it can be reduced to a multi-dimensional qualitative assessment – I now teach this assessment method as a 1 to 1.5 day training class as part of the Kanban Coaching Masterclass and the Enterprise Services Planning curricula.

If we look at the definitions for 2-star to 4-star Agile Fluency it is implicit that we need a more elaborate approach to defining and understanding value. In the original article (granted it is from 2012) there is broad hand-waving that this is a solved problem in Lean Startup or Lean Software Development. To be honest this isn’t realistic. Lean Startup would help you validate a hypothesis that value may exist. I am not really aware of anything in Lean Software Development that provides specific insights into analyzing value. However, the Lean Product Development body of knowledge, work by Reinertsen or Kennedy, does provide some methods. It has become quite trendy to define value using variants of Reinertsen’s approach to “cost of delay”. I still find this material nascent and problematic and analyzing why that is true is the subject of another on-going series of blog posts at this site which started with “What we know about duration: part 1“.

So moving up the Agile Fluency model to 2-star level implies we need better ways of defining value. We have had some methods for this in the Kanban body of knowledge since 2007 – for example, making qualitative assessment of cost of delay and assigning classes of service to work items. This is consistent with my analysis that kanban system and boards can take you to organizational maturity level 4 as described in my recent blog post, Kanban Patterns & Organizational Maturity. The risk assessment method which I have now formalized into the Enterprise Services Planning curricula rather than trying to bundle it with Kanban as we did between 2009 & 2014 provides a comprehensive, if admittedly qualitative, complex and non-deteministic method for both assessing value and selecting, sequencing and scheduling using value assessment. Most of this work, was available in publicly accessible form in 2012 though it doesn’t appear in a convenient book, but a significant portion of it appeared in my talk at the Agile 2009 conference.

The Trouble with “Kanban”

Reading the Agile Fluency article, we have to recognize that when Shore & Larsen say “Kanban” they actually mean “Team Kanban” – a topic considered so trivial in the Kanban community that Lean Kanban University didn’t bother to teach it or have a defined curriculum for it until 2015 with the introduction of Team Kanban Practitioner. In Kanban Patterns & Organizational Maturity I define Team Kanban as a maturity level 1 behavior. I do, however, point out that there are times where a single team delivers a recognizable and atomic service and isn’t merely part of a wider workflow involving multiple teams. In the case where a team delivers a service and it is self-contained to that team, then we would view them as being at organizational maturity level 2, providing the work items were customer-valued work items.

From this analysis, we begin to see a blurring of the lines. 1-star Agile Fluency could exist at organizational maturity level 1 though there does appear to be an implicit understanding that a “team” delivers a customer facing service and hence, there is an implication of organizational maturity level 2 but at a small team scale, not involving more elaborate workflow. There may even be a greater implicit assumption that if a longer more elaborate workflow were needed, then the people with these additional skills should be brought in to the team to maintain its integrity and encapsulation as a provider of a complete service.

It is a pity that Shore & Larsen do not appear to know more about Kanban and that they assume Team Kanban is all there is when in fact many years before 2012, we’d largely decided that Team Kanban was so trivial as to be not worth our effort even documenting it, nevermind teaching it. It is only in recent years with the recognition that so much of the market is at organizational maturity level 1 that we’ve decided to help bootstrap adoption by defining Team Kanban and associated training around it. In the Lean Kanban University, Team Kanban Practitioner, we do not assume maturity level 2. We do not assume a customer facing team with all the cross-functional skills embedded to deliver a turnkey service without dependencies. So for us, Team Kanban is very much at a “below Agile Fluency” level.

Technical Competency Improves

Where there is strong agreement between the models is at organizational maturity level 3 and 2-star Agile Fluency. With Kanban, and in the Kanban Management Professional (KMP) training and in the 5 chapter, section 4 of Kanban: Successful Evolutionary Change for your Technology Business, we look at ways of improving – improving delivery times for example. The Shore/Larsen model assumes that you can do this with Extreme Programming, which is a perfectly valid assumption, but it is one that comes with an agenda – you will adopt this Agile methodology. Kanban is anti-methodology. It is the “start with what you do now” and evolve method. In Kanban, we teach practitioners to identify opportunities for improvement and deploy specific practices, often Agile technical practices, in order to drive the improvement. Kanban uses model-driven improvement. Kanban also doesn’t assume a software development context. Regardless of the context, for example, advertising agencies or market research companies, we would expect technical competencies to improve in order to move through organizational maturity level 3.

The Trouble with Scaling

At 3-star Agile Fluency there is ambition to optimize economic outcomes. This is clearly a direct mapping with organizational maturity level 4. Where I differ from Shore & Larsen is in the manner and style of how this might be achieved. Their suggested approach is that you start adding the business functions to the team and the teams get larger and larger and more and more cross-functional. The Kanban approach to this is different. We use risk assessment to provide a common language for communication, collaboration and decision making. We believe that you don’t need to make teams larger and larger and more and more cross-functional in order to achieve collaboration. We believe collaboration comes from having a shared sense of purpose, unity, alignment and a common language for communication and a common framework for making decisions. Since 2014, I’ve chosen to package this in our Enterprise Services Planning training, rather than marketing it as “Advanced Kanban” as we were in the 2012-2014 time period. Kanban has been capable of taking organizations to maturity level 4 since 2007 and given the description provided, capable of taking more than just teams, but entire product or business units to 3-star Agile Fluency throughout the same time period. We already had a reference case study of Kanban on projects of over 50 people in 2007 and Kanban in use across an organization of 150 people with an annual budget of around $17 million. We weren’t playing with “teams” when it came to Agile fluency.

The Trouble with Optimizing

When I read Shore & Larsen’s description of 4-star Agile Fluency, I agree it is fair to say that Kanban hadn’t shown it could achieve all of this level, at their time of writing in 2012. However, a significant number of the attributes they describe were present and being reported within the Kanban community and at Lean Kanban conferences – use of Portfolio Kanban (for balancing risk and business initiatives), use of Upstream Kanban (for product management and real options), Operations Reviews as a product unit or business unit level, showing an understanding of a system of systems and how each independent workflow or project interacted and depended on others. This is all the more disappointing as Jim Shore had appeared at one of our conferences prior to the appearance of this 2012 article and there was plenty of such evidence all around him if he had cared to look.

What I can say now, is that I am quite confident that entire organizations can achieve 4-star Agile Fluency (and more) using Enterprise Services Planning.

Conclusions

It has proven important that I repackaged a lot of advanced and peripheral Kanban practices into Enterprise Services Planning because all too many agilists see or position Kanban only a team level method. If more senior leaders, and I include Shore and Larsen in this category, of the Agile community actually took the trouble to understand Kanban and what we’ve doing in the Kanban community over the past 8 years, they might come to realize we have a lot of answers, a lot of proven techniques, and that most of these concepts are complimentary and non-threatening to what they are already doing. Kanban and Enteprise Services Planning coupled to appropriate implementation of Agile technical practices can and will take you to a level of business agility that Shore & Larsen describe only as “aspirational.” If you have the aspiration to achieve 4-star Agile Fluency, we can take you there now, in 2016. And we can do all of this without reorganizing your business into massive, cross-functional teams. Kanban has never shared the Agile agenda of cross-functional teams. We believe in achieving collaboration through other means – shared language, transparency, visibility, shared decision making frameworks, fact-based, qualitative analysis techniques that drive consensus, customer focus, unity of purpose, and alignment.

I’d like to thank the client who asked for this evaluation and analysis, it was a useful and worthwhile exercise.

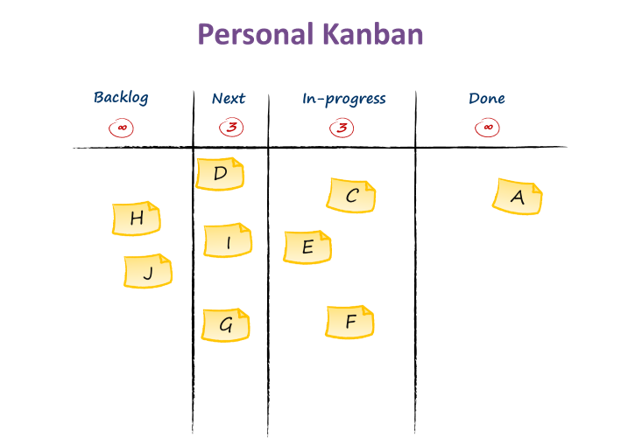

Figure 1. Personal Kanban

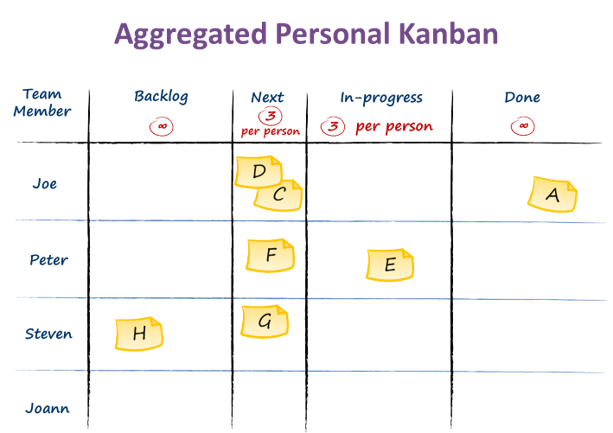

Figure 1. Personal Kanban Figure 2. Aggregated Personal Kanban

Figure 2. Aggregated Personal Kanban

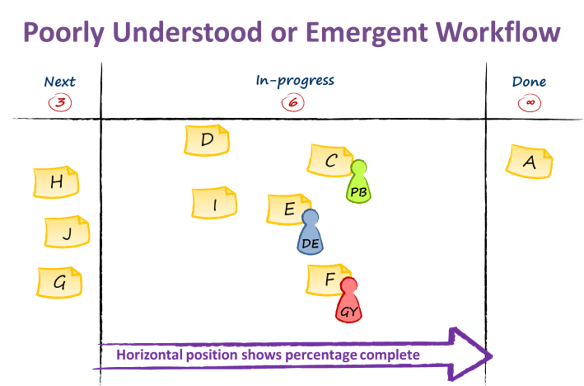

Figure 4. Emergent Workflow Board

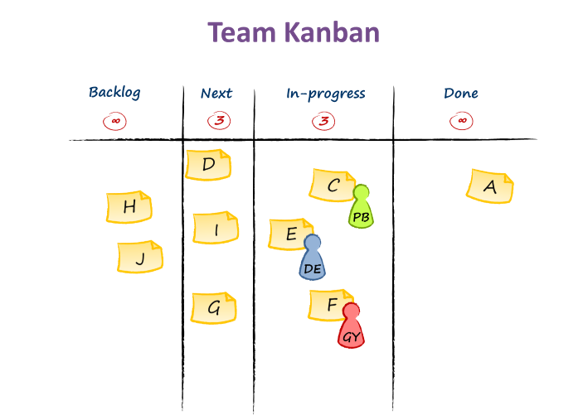

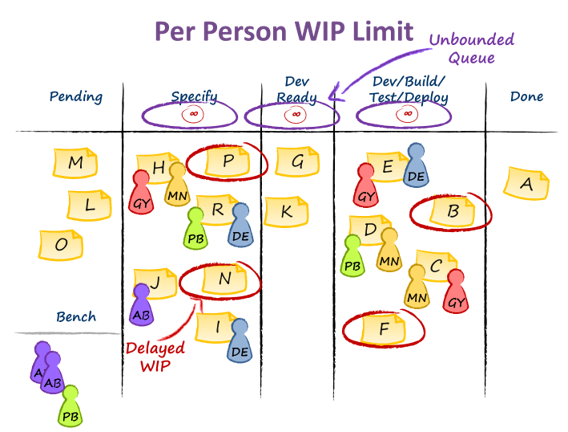

Figure 4. Emergent Workflow Board Figure 5. Per Person WIP Limit, Unconstrained Workflow

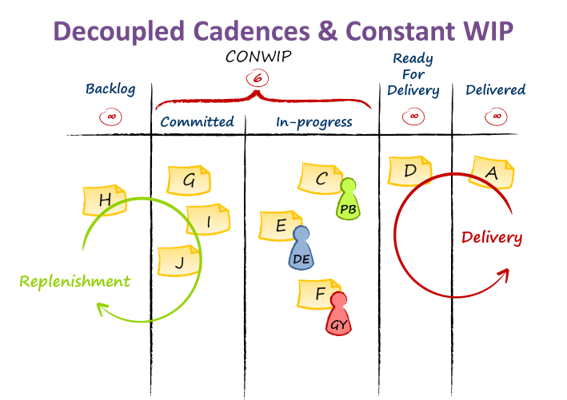

Figure 5. Per Person WIP Limit, Unconstrained Workflow Figure 6. CONWIP for a Team Kanban

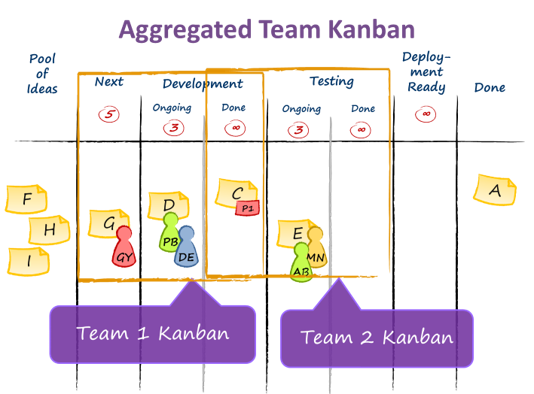

Figure 6. CONWIP for a Team Kanban Figure 7. Aggregated Team Kanban Board

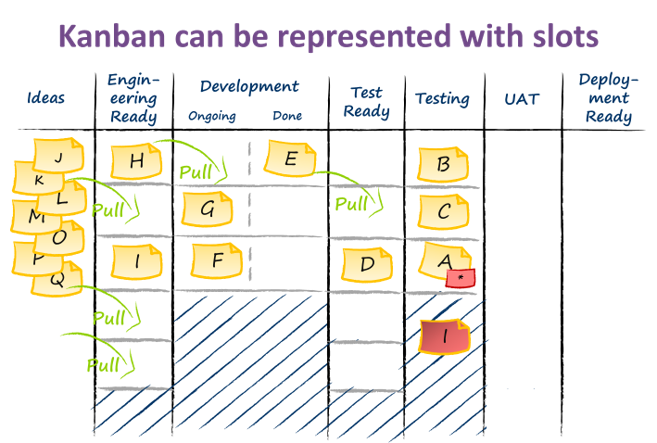

Figure 7. Aggregated Team Kanban Board Figure 8. Kanban board using phsyical space for kanban signals

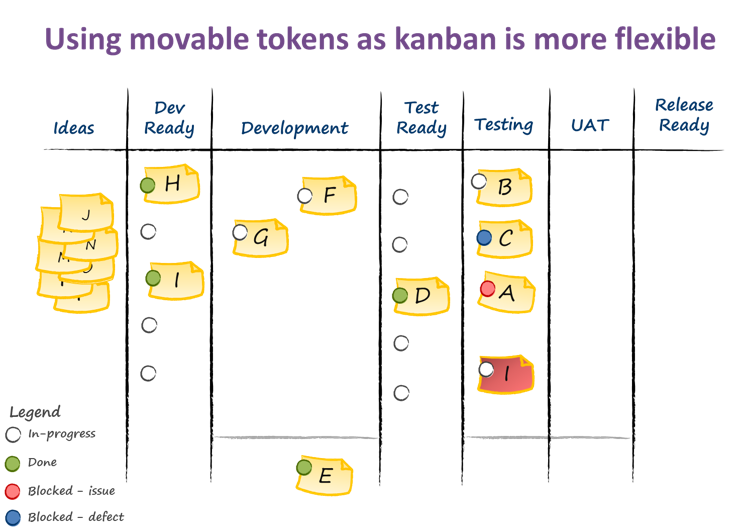

Figure 8. Kanban board using phsyical space for kanban signals Figure 9. Movable Token Kanban Board

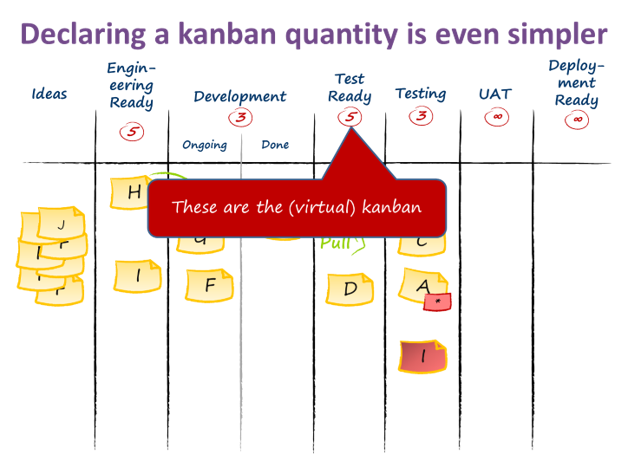

Figure 9. Movable Token Kanban Board Figure 10. A Virtual Kanban Board

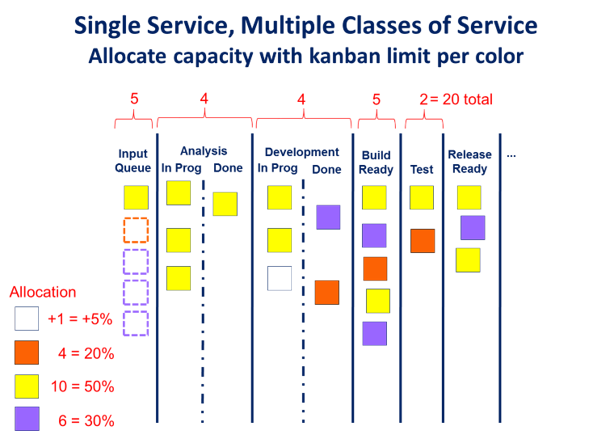

Figure 10. A Virtual Kanban Board Figure 11. Virtual Kanban with Classes of Service

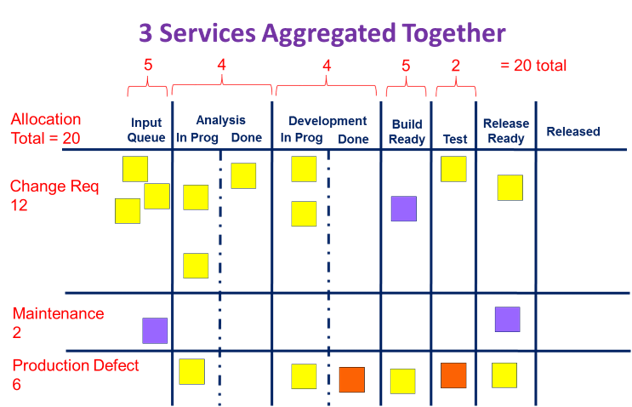

Figure 11. Virtual Kanban with Classes of Service Figure 12. Aggregated Services Virtual Kanban Board

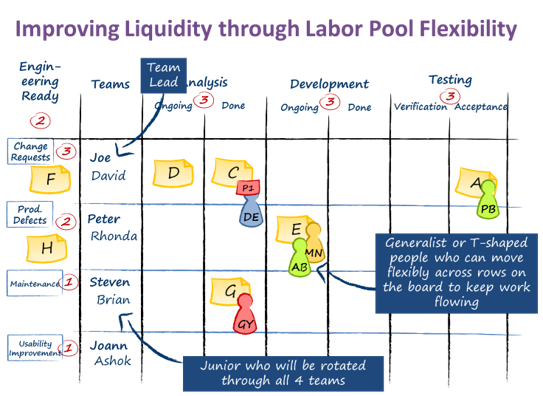

Figure 12. Aggregated Services Virtual Kanban Board Figure 13. Dedicated Teams Per Service with Flexible Staff Augmentation

Figure 13. Dedicated Teams Per Service with Flexible Staff Augmentation