In 2016, we are extending the Kanban Principles to specifically break out Service Delivery from Change Management as two sets of three. In the first of two posts on this I lay out the 2nd Edition of The Kanban Method, Change Management Principles.

Change Management Principles

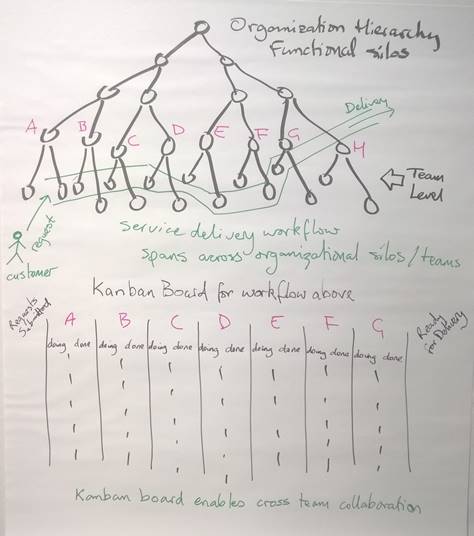

Your organization is a network of individuals, psychologically and sociologically wired to resist change to their identities, social structures and means of deriving self-esteem and social status. Resistance to change in the workplace often stems from how the changes affect individuals psychologically and sociologically. Kanban acknowledges these human aspects with its three change management principles:

- Start with what you do now

- understanding current processes, as actually practiced

- respecting existing roles, responsibilties and job titles

- Agree to pursue improvement through evolutionary change

- Encourage acts of leadership at every level

- from individual contributor to senior management

These principles represent The Kanban Method’s approach to change. An approach which has been adopted as a response to the complexity of the modern professional services workplace where workers perform knowledge work, producing intangible goods – a workplace where people are paid to think for their living and make decisions as opposed to carrying out manual activities under direction and supervision of a manager. In a knowledge worker workplace, management responsibility simply communicates authority to make decisions containing greater risk. In a knowledge worker workplace everyone makes decisions regardless of any supervisory responsibilities. These modern workplaces are inherently non-deterministic in nature. The system is complex and the outcomes it produces are emergent. 20th Century deterministic methods are outmoded. Kanban provides one new approach to process improvement and management for 21st Century businesses.

Start with what you do now

Most change management is based on a model introduced by the McKinsey consulting firm. This model became prevalent in the 20th Century and has two main flavors: replace what you are doing now with a defined process, prescribed from a catalog; design a replacement process customized to the dynamics of your environment. There is a variant of the second type where the design is based off the existing process as a baseline. There are several variants of these including Value Stream Mapping from the Lean body of knowledge, and the Thinking Processes approach from the Theory of Constraints. The Kanban Method rejects all of these approaches on the basis that they typically introduce too much change all at once, and they suppose that the process designer is somehow smarter than the workforce and smart enough to understand all the complexities of the domain and the dynamics of the workflow. This approach of designing solutions or selecting them from a pattern catalog seems to have worked fairly well in deterministic domains and physical environments. The Kanban Method is based on the assumption that such an approach is problematic in complex, non-deterministic domains such as professional services, knowledge work and creative pursuits. In other words, 21st Century businesses need a 21st Century model for change management. This model should be based on evolutionary theory as it is compatible with and robust to the complexity, emergent and non-deterministic outcomes of modern work producing intangible goods.

Specifically, “start with what you do now” is intended to reduce resistance to change from the people involved. Resistance to change is rooted in the identities of the individuals and the social groups to which they belong. Identity has psychology, social-psychological and sociological components to it. Identity and social position are often derived from practices performed. When we change these, we risk resistance. When we change the role and responsibilities of an individual or group of individuals, we risk resistance. If our goal is to make changes in order to improve service delivery, then we wish to avoid resistance to change.

Strategies for change are beyond the scope of Essential Kanban but we should recognize that our first strategy for managing change is always to avoid it when possible. So Ideally no one gets a new (professional) identity as part of a Kanban initiative. There are exceptions to this, if we introduce Service Delivery Manager or Service Request Manager roles but these are exceptions, not the rule.

Agree to pursue improvement through evolutionary change

Because The Kanban Method’s approach to change is so different from the 20th Century approaches involving defined or designed processes and defined transition initiatives in order to adopt the new way of working, it is important to gain agreement and understanding of the decision to pursue an evolutionary approach and agreement on what that means.

Evolutionary change means that in terms of a process definition, we are never done! There is no concept of “we have arrived” because we have adopted a set of practices and people are now behaving according to new role definitions and embracing new responsibilities. Instead, things will change little-by-little in response to need.

We understand those needs by understanding what makes a service “fit for purpose”. We define meaning metrics with threshold levels to reflect what represents “fit for purpose” in the eyes of the customer. Fitness criteria metrics define our desired capability. A gap between our current capability and the desired capability represent a driver for change. We can use analysis and modeling of our current processes to suggest changes. In this way we view Kanban as a model-driven and scientific approach to evolutionary change. It is directed evolution rather than random mutation of existing processes.

The concept of randomly mutating our existing processes would be compatible with The Kanban Method and is likely to resemble lower maturity, opinion-based change where gut feel rather than analysis and modeling are used to suggest the changes.

With Kanban we evaluate whether a change delivered an improvement by comparing the outcome against the desired fitness thresholds. If our capability has improved towards the desired levels then the change was an improvement and we should stick with it and probably amplify it. If the change resulted in a step back in capability then may consider rolling the change back or implementing another change, a roll forward of our process, in order to get back on track.

Encourage acts of leadership at every level

Change doesn’t happen unless someone cares, unless someone stimulates it to happen. The cover of the book, Kanban – Successful Evolutionary Change for your Technology Business features a cartoon with a character saying “Let’s do something about it.” This is an act of leadership!

Fundamentally what drives Kanban is the value of Customer Focus and the resultant leadership that comes from caring about improved service delivery and the resultant improvement in customer satisfaction.

Just as Kanban adopts a 21st Century evolutionary approach to change, because the domains are too complex, emergent and non-deterministic compared to 20th Century physical workplaces, equally Kanban believes that to drive change you need leadership at all levels. Seeing the opportunities for improvements and holding dissatisfaction about current capability should rightly be everyone’s business. The complexities of modern workplaces mean that it is unreasonable to delegate responsibility for process design and change management to a single person, department or representatives of a consulting firm. The Toyota culture of “kaizen” meaning “continuous improvement” is achieved by creating a culture where acts of leadership are encouraged and rewarded at all levels.

To encourage acts of leadership at all levels, leaders must lead by example. They must suggest changes. They must show the courage to speak up and experiment with changes. The culture must become experimental. There must be tolerance of the notion that not all changes are improvements. And that each change is an experiment until its results can be observed and analyzed. Failed experiments are not failures if the organization learned from it. If people fear being held accountable for failure then they will not show leadership. So to encourage acts of leadership at all levels not only must you lead by example, but you must create a culture of tolerance, understanding and patient, thoughtful inquiry.

Changing the culture isn’t a pre-requisite of Kanban, it should be part of the emergent outcome from practicing Kanban. The value gained, depth and maturity of your Kanban implementation will be constrained by your ability to embrace tolerance of failure, through thoughtful, patient, scientific inquiry and the ability of your workforce regardless of pay grade to feel safe making acts of leadership. Ultimately, there needs to be collective responsibility and accountability for service delivery and customer satisfaction, if you are to reach the highest levels of Kanban and reap its benefits.